Scientists from Texas A&M University and the U.S. Air Force say they’ve developed a process to 3D print the strongest kind of steel, along with other metals.

The process includes using a steel powder melted into place by a laser, this process follows in the footsteps of technologies like powder welding. In addition, with a mathematical model to gauge which laser settings will best reduce printing flaws, the researchers have made a process they claim makes strong steel into strong 3D-printed steel items.

The mathematical model and its results are presented as an “optimization framework” that anchors the team’s research

“This framework utilizes the computationally inexpensive Eagar-Tsai model, calibrated with single-track experiments, to predict the melt pool geometry,” the team writes. “Computationally inexpensive” means the mathematical model doesn’t require a lot of processing juice. Using this term usually indicates the new idea is an alternative that saves a ton of time compared to a traditionally iterating or permutating algorithm that can take, well, almost forever.

The results were striking right away. The team used its framework on a selective laser melting (SLM) additive sample made from especially corrosion-resistant steel called AF9628. From the paper’s abstract:

“Using this framework, fully dense samples were successfully fabricated over a wide range of process parameters, allowing the construction of an SLM processing map for AF9628. The as-printed samples displayed tensile strengths of up to 1.4 GPa, the highest reported to date for any 3D printed alloy.”

Why does introducing math make the steel so much stronger? The answer lies in some facts about steel itself and about 3D printing in general. The steel these researchers focus on, named martensite steel after the inventive 19th-century metallurgist Adolf Martens, is made in a process where extreme cooling traps carbon inside the structure of the steel. The overall category “carbon steel,” like a pan or car parts or the sharpest cutting implements, includes all martensite steels but is not exclusively martensite steels.

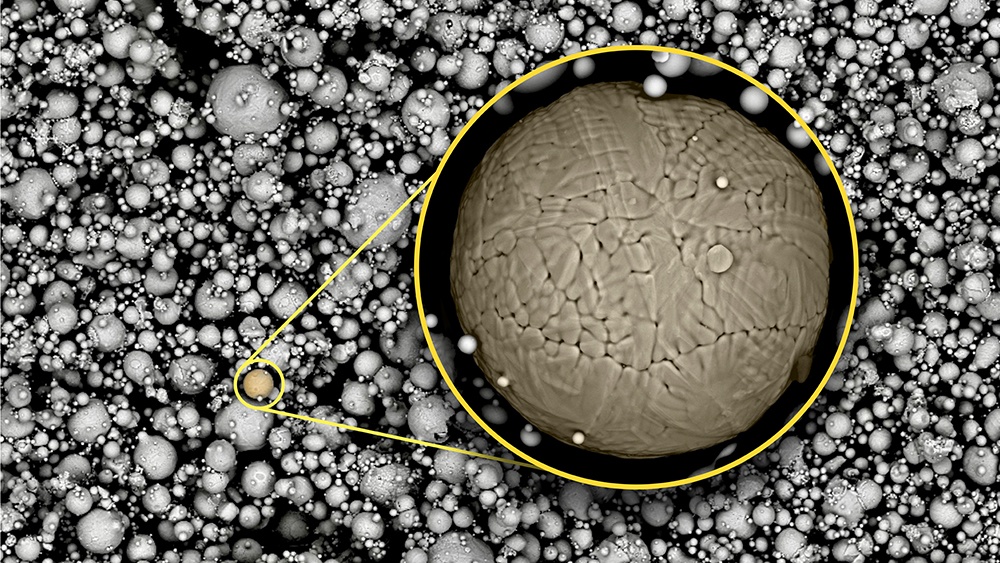

Carbon steels can already be quite brittle, and the techniques used in additive manufacturing—the technical term for 3D printing—can introduce flaws called porosities. “Porosities are tiny holes that can sharply reduce the strength of the final 3D-printed object, even if the raw material used for the 3D printing is very strong,” researcher Ibrahim Karaman explained.

To minimize porosities, the researchers used the large existing body of research about powder and other kinds of welding, where metal powder is heated to form the bonding agent between two pieces of metal. By varying the number of laser pulses per second and the power of the laser itself, the researchers adapted a welding model to begin developing and fine-tuning their 3D printing model. In subsequent iterations, they continued to tune, until their final model could tell in advance if certain settings would work well or not.

With this new research, steel manufacturers could save development time and wasted materials they might burn through while doing their own experiments with 3D printing—or, more likely, it could lure them into the realm of 3D printing at all. Adding ultrahard carbon steel to the 3D printing repertoire could be a huge boon for the industry, from the most established old companies to rocket-printing startups.