New modeling software is helping animal health experts develop more customizable prosthetics for pets with missing limbs. Still, not all legs are created equal.

Condider the three-legged dog. Perhaps you own one, or have seen them in the park or in any of the billions of Dodo videos about them. Lopsided yet resilient, they evoke a kind of fawning sympathy from us humans that’s unmatched by the typical quadruped canine.

“People are drawn to specially abled pets,” says Rene Agredano, a cofounder of the pet-amputation support website Tripawds. “I think the attraction is that we just want to help them. We just want to make sure that they are given an equal chance at having a happy life.”

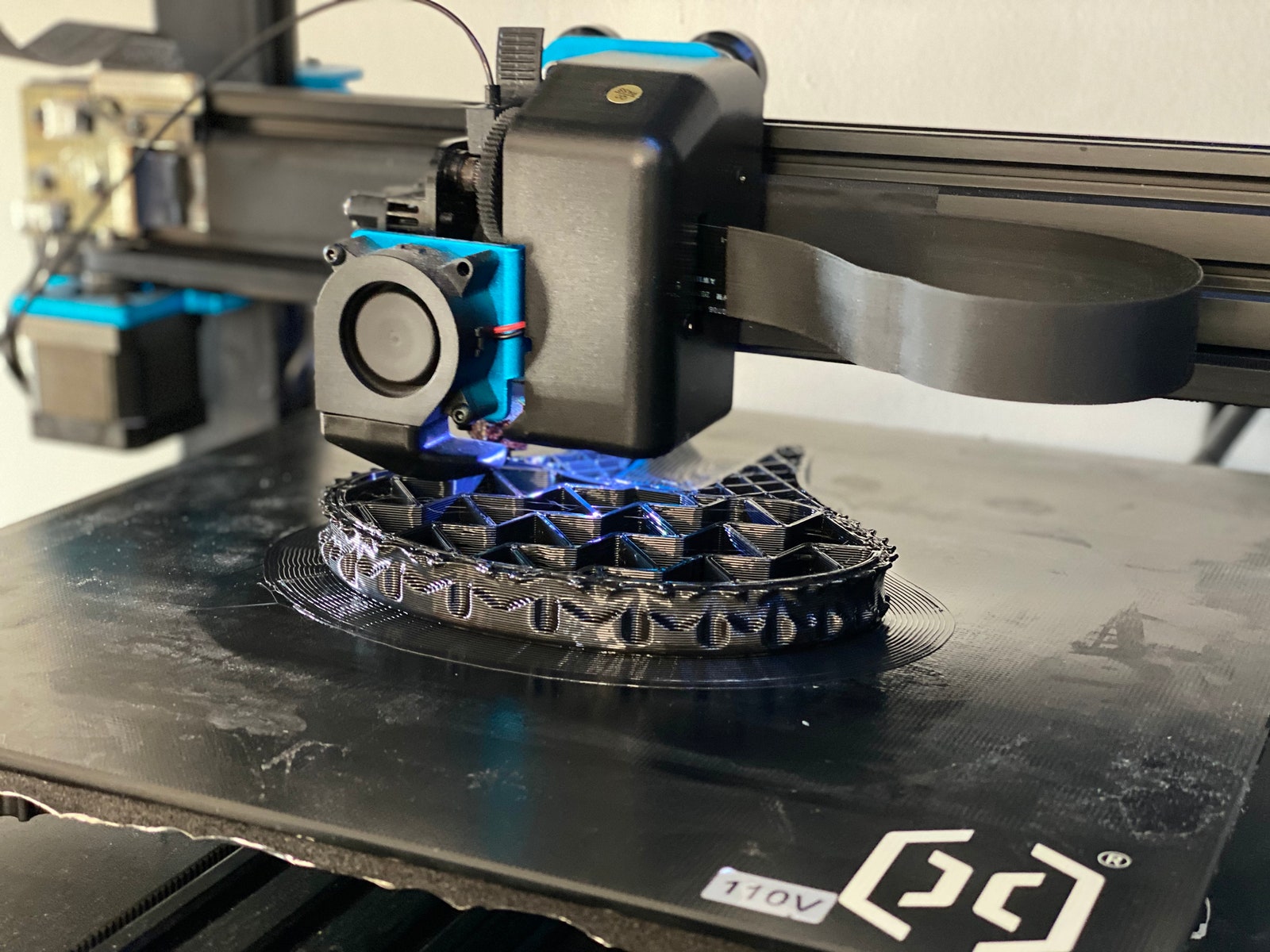

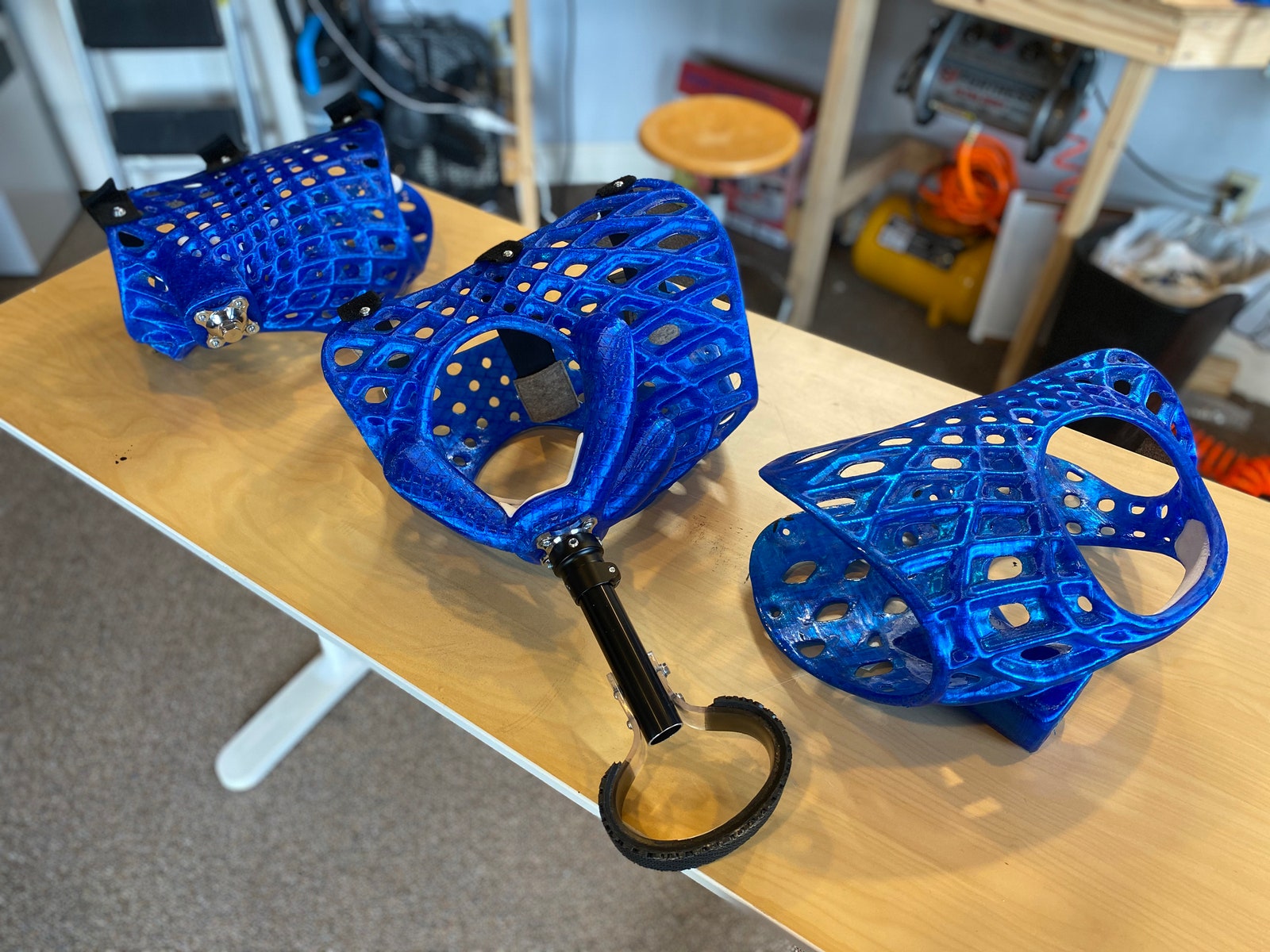

More and more, that desire to help manifests as prosthetics, especially in cases where the animal has lost more than one limb. Pets with artificial limbs have become a whole genre of feel-good videos of their own. A cat with bionic hind legs. A tortoise with wheels. The clips make the rounds on Facebook, where they add a smidge of feel-good optimism to the otherwise dour deluge that is your newsfeed. 3D printing has propelled the industry forward. Printed prosthetics can be lightweight, affordable-ish, and infinitely customizable. Doctors craft beaks for birds. High school students build artificial dog legs in their free time.

But not all pet prosthetics are created equal. And some veterinarians and people in the tripod community worry that the proliferation of easily craftable attachments could lead to unintended consequences for the critters that wear them.

Walking Distance

Dogs can lose a limb for a variety of reasons. Maybe they were born with an abnormal limb, or were hit by a car, or developed a cancerous growth that necessitated an amputation. A common quip among tripod lovers is that “dogs have three legs and a spare.” It’s true, to a point. Dogs adapt remarkably well to losing a limb, says Theresa Wendland, who specializes in animal sports medicine and rehabilitation at the Colorado Veterinary Specialist Group. But complications can arise as the animal compensates for what’s missing. In older dogs and dogs with arthritis or other mobility issues, putting extra weight on the remaining limbs can be a big problem.

Markforged Mark Two

- High-Strength Printing: Reinforce your parts with composite fiber while 3D printing then and go unparalleled strength, stiffness and durability.

- Range of Materials: Prints in Carbon Fiber, Fiberglass, Kevlar and Onyx.

- Easy-to-Use: Equipped with its own Markforged Eiger software that is both powerful and easy to use in your browser, importing your drawing and slicing it for high strength printing.

- Touchscreen Interface: Easily connect to wifi, start prints and manage your printer.

- Precision Design: Pause/resume prints, remove the bed and add components thanks to a click-into-place bed with 10 micron accuracy.

“It really impacts their spinal mobility,” Wendland says. “They have to change the range of motion in their other limbs. They have to pull themselves forward in ways that are very unnatural.”

Prosthetics, if made right, can restore that range of motion. But as heart melting as it is to see a three-legged dog return to running on four legs, it’s not easy to build a proper puppy peg leg. Wendland, who works with the orthopedic and prosthetic company OrthoPets to help dogs adapt to their new limbs, says that it’s an involved process that takes time and technical know-how.

As with human prosthetics, an animal prosthetic has to be individually tailored to the build of the wearer. That means factoring in the animal’s size, weight, height, stance, and gait. (A kit for a doberman won’t fit on a dachshund.) To do that, orthopedists have to study the animal’s movements and try to mold a limb that will sync up with the others. While techniques vary, a standard process is to make a plaster cast, design the prosthetic based on photos and video, then build it out with durable thermoplastics and metal. From there, they tweak the finer details by hand until it works with the animal. The process can take weeks.

There’s also the matter of the amount of the limb that needs replacing. The ideal spot to put a prosthetic, Wendland says, is as low on the limb as you can go. But if the whole limb is gone and there’s no obvious point to attach a prosthetic, it gets much trickier.

A Leg Up

3D printing has long been hailed as a manufacturing revolution in many industries, prosthetics among them. And now, a New Jersey–based design firm called Dive Design thinks it’s the solution to full-limb replacement. It has partnered with a company called Bionic Pets that builds exactly what its name implies: accessibility tech for pets. Derrick Campana, who runs Bionic Pets, has long built pet prosthetics by hand. (He’s even got a show about it called The Wizard of Paws, which airs on Brigham Young University’s television channel.) About a year ago, he invited Dive Design heads Alex Tholl and Adam Hecht to his lab in Virginia to look at how he could improve the process.

Dive Design’s process is similar to building standard orthopedics: Study the dog, take measurements, model it out, and then build from there. But 3D printing lets the engineers quickly adapt and change the physical product in ways that are far less feasible with traditional prosthetics. If a particular joint or lattice that makes up a support isn’t working, they can rework it in a matter of hours.

Bionic Pets’ Campana says the rapid iteration afforded by 3D printing is especially beneficial for younger animals, since the patient may need many devices as its body grows. “A new device may be needed, but we do not need to make a cast or redesign,” he says in an email. “We can just resize the file and reprint.”

“I’m kind of borderline obsessed with this kind of work,” Aira, who works on modeling and developing the prosthetics, says. “We’re really just scratching the surface of how we think about 3D printing and how we think about everything around us. It’s really amazing what we’re going to be able to do and how we’re going to be able to take advantage of these technologies.”

While that enthusiasm may be in high supply, labor and expertise doesn’t come cheap. Wendland says the prosthetics on which she’s consulted typically fall somewhere between $1,800 to $2,000. Bionic Pets’ prices are still expensive, but more reasonable: $850 for a partial limb and $1,750 for a full limb. These hefty price tags may be familiar to pet owners who have experienced the sticker shock of an astronomical vet bill. So the ability to make inexpensive prosthetics is no doubt appealing.

“What makes me a little nervous about 3D printing is that people start to get this idea that anybody can make a prosthetic,” Wendland says. “I just see potential for harm with something like that. I love that people are excited about it and that they want to help, but there’s a lot that has gone into the training and the people who are actually doing this for a living and making this happen in a functional way.”

An animal might look cute with its artificial limb in an Instagram video, but if that prosthetic hasn’t been carefully crafted by people with the orthopedic knowledge to properly customize it, there’s a risk of it causing more harm than if there was no prosthetic at all. Let’s say a dog moves with the assistance of a wheeled cart. If the wheels are placed too far back, it can create excess stress on the spine. Place them too far forward, and the dog’s constantly tipping over onto its face. A leg prosthetic that doesn’t fit properly can cause sores and ulcerations where the bone meets the skin, sometimes resulting in internal damage in the leg.

Prosthetic builders like Dive Design, Bionic Pets, and Ortho Pets have to work in close consultation with orthopedic veterinarians to ensure that their creations aren’t actively detrimental to the animal. Pet prosthetics are a new enough phenomenon that there isn’t a lot of research to definitively show what works and what doesn’t. For now, orthopedic surgeons and builders just have to rely on clinical experience.

Regardless of the type of prosthetic, one thing the animal can’t avoid is the need for rehabilitation. It can take weeks or months of physical rehab for a dog to become comfortable with a prosthetic. That means more vet visits, more investment and expenses.

Wendland hasn’t worked with Dive Design’s models specifically, but she says these types of full-limb assistive devices have their place. But it’s important for every pet owner who finds themselves considering one to know their options.

“Depending on the situation, I almost wonder if that money wouldn’t be a little bit better spent towards good rehabilitation,” Wendland says. “Maybe acupuncture for secondary muscle soreness, things like that, to keep a dog mobile. But I would absolutely consider these for a dog where they have problems with the other leg. I think this is a great use of 3D printing.”